Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), which mainly occurs in children, involves weakness of the arms and legs and may include other symptoms such as inability to breathe or swallow. There have been outbreaks of AFM in the US in 2014, 2016, and 2018, mainly in the late summer and early fall. The outbreaks of AFM are associated with infection with enteroviruses.

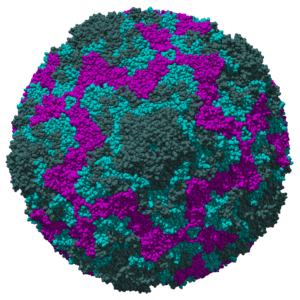

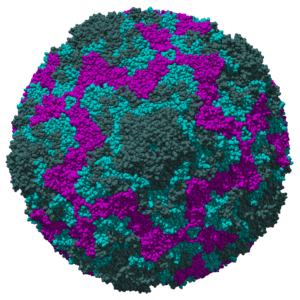

AFM was first defined in 2014 after reports of limb weakness in children across the US during an outbreak of respiratory disease caused by EV-D68 (pictured). AFM may also be associated with infections caused by other viruses, such as enterovirus A71, Coxsackievirus A16, West Nile virus and adenovirus.

Of the 233 patients with confirmed AFM in 2018, EV-D68 was the most frequently detected virus, mainly in respiratory samples. Confirming a viral etiological agent of AFM would be greatly strengthened by finding virus in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). However in 2018 only two samples of cerebrospinal fluid from AFM patients were found to be positive for viral RNA: one for EV-D68 and one for EV-A71. There may be multiple reasons for the failure to detect viral RNA in CSF, including clearance of virus by the time AFM is diagnosed, or very low levels of viral genomes.

An alternative to searching for viral genomes in CSF is to identify anti-viral antibodies, which may be produced during infection of the brain and spinal cord. Peptide microarrays were used to detect antibodies against enteroviruses in CSF of AFM patients. In this method, 160,000 unique peptides from the capsid proteins of all known human enteroviruses were spotted on slides. CSF samples were incubated with the slides and binding of antibodies to peptides was quantified. The results revealed antibodies to an 18 amino acid peptide of capsid protein VP1 in serum and CSF of 11/14 AFM patients and 3/26 controls. This amino acid sequence is known to be conserved among diverse human enteroviruses.

More importantly, antibodies to a 22 amino acid sequence in VP1 of EV-D68 were identified in CSF of 6/14 AFM, and in 8/11 serum samples. No immunoreactivity to this peptide was detected in samples from 26 controls.

Detection of antibodies in the CSF is not diagnostic of CNS infection because antibodies are known to pass from blood to CSF. The normal ratio of antibodies in blood to CSF is 250:1. Consequently, for diagnostic purposes, both serum and CSF should be analyzed for the presence of antibodies.

The authors of the study acknowledge this issue, noting that they do not have sufficient simultaneously collected serum and CSF samples to exclude that antibodies they detected in the CSF simply came from the blood. They note that of the 16 control patients with serum antibodies to enteroviruses, only 3 also had such antibodies in CSF. Furthermore, in a study of unexplained encephalitis in India, of 77 children with serum antibodies to enteroviruses, only 3 also had EV antibodies in CSF. For these reasons the authors do not believe that the anti-EV-D68 antibodies they have detected in CSF have come from the blood.

How can it be definitively proven that EV-D68 causes AFM? With an outbreak of AFM expected in the late summer of 2020, there should be ample opportunity to obtain numerous clinical samples – nasopharyngeal wash, serum and CSF – to examine for the presence of EV-D68 antibodies and viral genomes.

Pingback: Enterovirus D68 and childhood paralysis – Virology Hub