History

Zika virus was first identified in 1947 in a sentinel monkey that was being used to monitor for the presence of yellow fever virus in the Zika Forest of Uganda. At this time cell lines were not available for studying viruses, so serum from the febrile monkey was inoculated intracerebrally into mice. All the mice became sick, and the virus isolated from their brains was called Zika virus. The same virus was subsequently isolated from Aedes africanus mosquitoes in the Zika forest.

Serological studies done in the 1950s showed that humans carried antibodies against Zika virus, and the virus was isolated from humans in Nigeria in 1968. Subsequent serological studies revealed evidence of infection in other African countries, including Uganda, Tanzania, Egypt, Central African Republic, Sierra Leone, and Gabon, as well as Asia (India, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia).

Zika virus moved outside of Africa and Asia in 2007 and 2013 with outbreaks in Yap Island and French Polynesia, respectively. The first cases in the Americas were detected in Brazil in May 2015. The virus circulating in Brazil is an Asian genotype, possibly imported during the World Cup of 2014. As of this writing Zika virus has spread to 23 countries in the Americas.

The virus

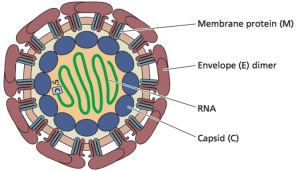

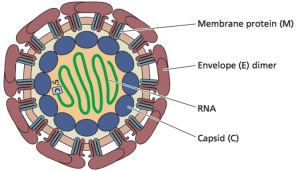

Zika virus is a member of the flavivirus family, which also includes yellow fever virus, dengue virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and West Nile virus. The genome is a ~10.8 kilobase, positive strand RNA enclosed in a capsid and surrounded by a membrane (illustrated; image copyright ASM Press, 2015). The envelope (E) glycoprotein, embedded in the membrane, allows attachment of the virus particle to the host cell receptor to initiate infection. As for other flaviviruses, antibodies against the E glycoprotein are likely important for protection against infection.

Transmission

Zika virus is transmitted among humans by mosquito bites. The virus has been found in various mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, including Aedes africanus, Aedes apicoargenteus, Aedes leuteocephalus, Aedes aegypti, Aedes vitattus, and Aedes furcifer. Aedes albopictus was identified as the primary vector for Zika virus transmission in the Gabon outbreak of 2007. Whether there are non-human reservoirs for Zika virus has not been established.

Signs and Symptoms

Most individuals infected with Zika virus experience mild or no symptoms. About 25% of infected people develop symptoms 2-10 days after infection, including rash, fever, joint pain, red eyes, and headache. Recovery is usually complete and fatalities are rare.

Two conditions associated with Zika virus infection have made the outbreak potentially more serious. The first is development of Guillain-Barre syndrome, which is progressive muscle weakness due to damage of the peripheral nervous system. The association of Guillain-Barre was first noted in French Polynesia during a 2013 outbreak.

Congenital microcephaly has been associated with Zika virus infection in Brazil. While there are other causes of microcephaly, there has been a surge in the number of cases during the Zika virus outbreak in that country. Whether or not Zika virus infection is responsible for this birth defect is not known. One report has questioned the surge in microcephaly, suggesting that it is largely attributed to an ‘awareness’ effect. Current epidemiological data are insufficient to prove a link of microcephaly with Zika virus infection. Needed are studies in which pregnant women are monitored to see if Zika virus infection leads to microcephaly.

Given the serious nature of Guillain-Barre and microcephaly, it is prudent for pregnant women to either avoid travel to areas that are endemic for Zika virus infection, or to take measures to reduce exposure to mosquitoes.

Control

There are currently no antiviral drugs or vaccines that can be used to treat or prevent infection with Zika virus. We do have a safe and effective vaccine against another flavivirus, yellow fever virus. Substituting the gene encoding the yellow fever E glycoprotein with that from Zika virus might be a good approach to quickly making a Zika vaccine. However testing of such a vaccine candidate might require several years.

Mosquito control is the only option for restricting Zika virus infection. Measures such as wearing clothes that cover much of the body, sleeping under a bed net, and making sure that breeding sites for mosquitoes (standing water in pots and used tires) are eliminated are examples. Reducing mosquito populations with insecticides may also help to reduce the risk of infection.

Closing thoughts

It is not surprising that Zika virus has spread extensively throughout the Americas. This area not only harbors mosquito species that can transmit the virus, but there is little population immunity to infection. Infections are likely to continue in these areas, hence it is important to determine whether or not Zika virus infection has serious consequences.

Recently Zika virus was identified in multiple states, including Texas, New York, and New Jersey, in international travelers returning to the US . Such isolations are likely to continue as long as infections occur elsewhere. Whether or not the virus becomes established in the US is a matter of conjecture. West Nile virus, which is spread by culecine mosquitoes, entered the US in 1999 and rapidly spread across the country. In contrast, Dengue virus, which is spread by Aedes mosquitoes, has not become endemic in the US.

We recently discussed Zika virus on episode #368 of the science show This Week in Virology. You can be sure that we will revisit this topic very soon.

Added 1/28/16 9:30 PM: The letter below to TWiV provides more detail on the situation in Brazil.

Esper writes:

Hi TWIVomics

I hope this email finds you all well and free of pathogenic viruses.

My name is Esper Kallas, an ID specialist and Professor at the Division of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, University of São Paulo, Brazil.

I have been addicted to TWIV since a friend from U. Wisconsin participated in the GBV-C episode (David O’Connor, episode #260). Since then, never missed one episode. After long silent listening, I decided to write for the first time, motivated by the ongoing events in my country, potentially related to the Zika virus.

In the last episode, Emma wrote about events taking place in the small town of Itapetim, State of Pernambuco, Northeastern Brazil, which I will describe a bit later in this email. Before, let me bring some background information on the current situation.

Most believed Zika was a largely benign virus, causing a self-limited disease, clearly described in episode #368. Its circulation was documented after an outbreak became noticed in the State of Bahia (NE Brazil) by a group led by Guilherme Ribeiro, a talented young Infectious Diseases Scientist from Fiocruz (PMID: 26584464, Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Dec;21(12):2274-6, free access)

However, things started to get awkward around October 2015, when a single hospital in Recife (NE Brazil) and some other practicing Obstetricians and Pediatricians from the region started reporting a mounting number of microcephaly cases in newborns, later confirmed by the national registry of newborns. The numbers are astonishing. The graph below depicts the number of cases per year prior to the surge in 2015. Only this year, 2,975 cases were reported by December 26, the vast majority in the second semester of the year. Cases are concentrated in the Northeast (map), with 2,608 cases, including 40 stillbirths or short living newborns.

In response to the situation, the Brazilian Ministry of Health has declared a national public health emergency (http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/cidadao/principal/agenciasaude/20629-ministerio-da-saude-investiga-aumento-de-casos-de-microcefalia-em-pernambuco).

The Brazilian Ministry of Health has been presenting updates every week (see link: http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/o-ministerio/principal/leia-mais-o-ministerio/197-secretaria-svs/20799-microcefalia). It is important to observe some imperfections in these numbers: 1. There may be an over reporting after the news made to the big media, suggesting an association between microcephaly and Zika virus. 2. The criterion to consider a microcephaly case has been changed after the current epidemic from 33cm to 32cm; this is because 33cm of head circumference is sitting in the 10th percentile of newborns at 40 weeks of pregnancy and the adjustment would bring the limit to the 3rd percentile, increasing the specificity to detect a true microcephaly case (this may result in an over reporting in the beginning of the epidemic).

The association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly was suspected since the beginning, when Brazilian health authorities ruled out other potential causes, together with the fact that the microcephaly epidemic followed Zika virus spread. Further evidences were the two positive RT-PCR for Zika RNA in two amniotic fluids obtained from two pregnancies of microcephalic fetuses and a stillborn microcephaly case with positive tissues for Zika RNA. In fact, French Polynesia went back to their records and also noticed an increase of microcephaly case reporting, following their epidemic by the same virus strain in 2013 and 2014.

Now, Zika virus transmission has been detected in several countries in the Americas (http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_topics&view=article&id=427&Itemid=41484&lang=en).

Although strong epidemiological data suggest the association between Zika virus and the microcephaly epidemic, a causal link between the virus and the disease is still lacking and is limited to few case reports. Many questions still remain. Does the virus damage embryonic neural tissue? What is the percentage of fetuses getting infected when the mother acquires Zika virus during pregnancy? Does the stage of pregnancy interfere with virus ability to be transmitted to the fetus and the development of neurologic effects? Are there other neurological defects related to Zika virus infection? Is there another cofactor involved, such as malnutrition or other concurrent infection? All these questions are exceedingly important to provide counseling to pregnant women and those who are planning to become pregnant, especially in Northeastern Brazil. In fact, Brazilian authorities have been recommending avoiding pregnancy until this situation is further clarified.

The microcephaly epidemic impact is unimaginable. It is a tragedy. These children are compromised for life and the impact on their families is beyond any prediction.

Back to the story sent by Emma. A small town in the North of Pernambuco State, named Itapetim, has almost 14 thousand inhabitants and has reported 11 cases of microcephaly in the past 3 months. This very same town has been suffering from a prolonged drought, since September 2013 when the last reservoir went dry. Perhaps the storage of clean water or the limited resources has led to the best environment for arbovirus spread and the development of microcephaly.

But the Zika virus’s impact may be reaching further. An increase in Guillain-Barre syndrome cases has also been noticed in the Northeast of Brazil, possibly related to the epidemic.

Several groups have been trying to establish animal models to study the interaction of Zika virus with neural tissue. The forthcoming developments are critical to better understand the virus immunopathology and confirm (or refute) the association between the virus infection and neurologic damage in fetuses and in the infected host developing Guillain-Barre syndrome. Many things still shrouded in mystery.

Keep on the good work. I will keep on listening!

Esper

The link to the “One report has questioned the surge in microcephaly, suggesting that it is largely attributed to an ‘awareness’ effect.”

http://www.nature.com/news/brazil-s-surge-in-small-headed-babies-questioned-by-report-1.19259

Flavivirus is not a family of viruses, is a genus..

Splitting hairs? Flaviviridae for the family.

Does anyone know if there is cross-reactivity between Zika and Dengue virus?

Pingback: Zika virus | Media Cultures: Microbiology in th...

Yes, there is cross-reactivity between Zika and dengue viruses, which complicates diagnosis by serology.

Flavivirus is the family. One can use the word ‘Flaviviridae’ to indicate the family, or flavivirus family. Flavivirus also happens to be the genus name. In a similar way, we say Picornaviridae, or picornavirus family.

For the Zika virus, is it better to make attenuate vaccine than killed vaccine? Does the Zika have an IRES site? Can you make a ZIKV vaccine base on the disrupted IRES site?

I wonder if there is a way to use zika as a vaccine against dengue, since the symptoms are much milder. Of course we need to study more the biology of the virus, mainly went it can cause auto immune disease. As an example of the use of a related virus as a vaccine for another virus is the vaccinia being used against smallpox.

Excellent summary, thank you.

Pingback: Zika virus was first identified in 1947 in a sentinel monkey that was being used to monitor for the presence of yellow fever virus in the Zika Forest of Uganda. | Vaccine Common Sense

A dengue vaccine already exists and was just released recently.

“There is substantial serological cross-reactivity between the flaviviruses and current IgM antibody assays cannot reliably distinguish between Zika and dengue virus infections. Therefore an IgM positive result in a dengue or Zika IgM ELISA test should be considered indicative of a recent flavivirus infection. Plaque-reduction neutralization tests (PRNT) can be performed to measure virus-specific neutralizing antibodies and may be able to discriminate between cross-reacting antibodies in primary flavivirus infections. For primary flavivirus infections, a fourfold or greater increase in virus-specific neutralizing antibodies between acute- and convalescent-phase serum specimens collected 2 to 3 weeks apart may be used to confirm recent infection. In patients who have been immunized against (e.g., received yellow fever or Japanese encephalitis vaccination) or infected with another flavivirus (e.g., West Nile or St. Louis encephalitis virus) in the past, cross-reactive antibodies in both the IgM and neutralizing antibody assays may make it difficult to identify which flavivirus is causing the patient’s current illness.”

From: CDC, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Arboviral Diseases and Dengue Branches ( http://www.cdc.gov/zika/pdfs/denvchikvzikv-testing-algorithm.pdf )

Here in Brazil, a big part of our population had been vacinated against yellow fever and/or had Dengue. This, associated with the small number of symptomatic cases, it is a big challenge for an accurate diagnosis

Pingback: How does Zika virus shrivel a baby's brain and other FAQs - PBS NewsHour - Good Brain

Pingback: How does Zika virus shrivel a baby’s brain and other FAQs | Breaking World News

Pingback: The children of Zika: Babies born with disorder linked to virus – Ghost2Ghost.Org

Pingback: How does Zika virus shrink a baby's brain and other FAQs - PBS NewsHour - Virus Remover

Pingback: ‘”ALERT” ”Zika virus” stay in all world↓↓↓Video Here↓↓↓ – HOTNEWSVIDEOS

1) Why not measure circumference at eye-level and, say, 8 or 10cm above that for a ratio? The current method even with reduction of 1 cm does not reflect the way the head shape is affected. 2) Perhaps, a meaningless observation — a long shot — but in a pre-WWII book of fotos of Bali (and maybe java too, I forget) I recall one of a young man with what I would have called a pinhead who was kept chained to a stake by a shackle around an ankle and was called a monkey-man by the locals! So I wondered if there are microcephaly records for Indonesia and whether it is possible the virus comes from there rather than Africa … 3) Because maybe a million of us in Florida have no health insurance and do not see doctors (the Republicans blocked Medicaid for poor people that the federal gov’t would have applied to keep out ridiculously expensive insurance affordable), I would not be surprised to see whatever happened in Brazil happen here, esp w/ the Republicans trying to prevent abortion and make it hard for women to get birth-control. by attacking Planned Parenthood in both states.

Pingback: How does Zika virus shrink a baby’s brain and other FAQs | Lovehealth.science

Pingback: How does Zika virus shrink a baby’s brain and other FAQs – All About Zika Virus

Pingback: What You Need to Know About the Zika Virus | Breaking World News

Pingback: What You Need to Know About the Zika Virus | Vus Times

Pingback: What You Will need to Know About the Zika Virus - Feeling Sick

Pingback: What You Need to Know About the Zika Virus

Pingback: What You Want to Know About the Zika Virus - Feeling Sick

Pingback: What You Need to Know About the Zika Virus - Huffington Post - BrdCloud News

Pingback: What You Need to Know About the Zika Virus – Total Wellness Daily

I am not a virologist, but offer the following:

• Little is known about the etiology of microcephaly with Zika as an initiating event. However, it is known that microcephaly can result when there is a deficiency of GLUT-1, a transporter of glucose across the blood-brain barrier. This can result in lower levels of glucose in the CSFl fluid even when there is more than adequate glucose in the blood.

• Add to this the finding that the related Dengue Fever has been reported to reduce GLUT-1 on the neutrophil cell membrane. Is there some commonality here by which Zika affects glucose transport across the blood brain barrier??

• Microcephaly can also be brought about when there are specific nutrient deficiencies. Is there some aspect to Zika viral expression that affects utilization of nutrients involved at key periods of cephalic development?

Pingback: What You Need to Know About the Zika Virus | women times

Pingback: How worried should you be about Zika virus? - UofMHealthBlogs.org

Pingback: Zika from sex is the byway, not the highway

somebody in the theater has yelled “FIRE”. if the Zika virus caused microephaly, then this would have turned up in Africa long ago. the virus has been widespread there since the 1950s. the real problem is that now people are demanding more chemicals being sprayed to kill mosquitoes. more chemicals in the environment HAS been proven to cause birth defects, cancer etc.

Pingback: Zika from sex, the byway but not the highway – Medical Microbiology Research Center

Unless it was endemic in those areas, so people got it when they were younger, before they had kids. Kind of like 5th disease in the US, which can be devastating if you get it while pregnant, but is very mild as a child, when most people get it.

but there is no evidence that shows a link between the zika virus and microcephaly. the whole hubbaloo is based on one community in Brazil, which has been in drought since 2013, conditions that favor the arbovirus, which has been proven to cause microcephaly. (tics carry it, not mosquitoes.)

Pingback: Zika virus and microcephaly

Pingback: Zika virus | Tools and tips for scientific tink...

Pingback: What The Heck Is This Zika Virus? – The Parkman Post

Pingback: Zika virus and the fetus

Pingback: What You Need to Know About the Zika Virus – All About Zika Virus

Hi, this post is truly nice and I have learned lot of things from it about blogging,thanks for sharing…

What countries should pregnant women avoid?

About two dozen destinations mostly in the Caribbean, Central America and South America.The Pan American Health Organization believes that the virus will spread locally in every country in the Americas except Canada and Chile…..http://bit.ly/1WdSRr5

ZIKA VIRUS: HOW TO AVOID PREGNANCY WHILE MAINTAINING SEXUAL INTIMACY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Sxg1L4CYzw

How to Recognize Zika | vick physiotherapy amsterdam

https://vickphysiotherapy.wordpress.com/2016/03/10/how-to-recognize-zika/

Thanks for the informative post! Since the recent outburst

of Zika in the U.S, do you think we will continue to see more infected persons

in the coming months/years?

It’s frightening to know that this virus has been around for so long but very

few people knew about it. I only heard about the Zika virus when people started

becoming infected in the U.S. I think it’s important to be aware of these

deadly and dangerous viruses around the world. We shouldn’t become aware of it

only when it affects someone in the U.S. People are traveling to different

countries every day and should be better educated on how to avoid contact and

decrease their risk of acquiring these harmful viruses.

I am very interested in the show you mention in your post. What station is it on and when do they play

it?

Zika surely is dangerous and there are many myths about this vrius. Thanks for sharing such great information. For hidden facts about zika- http://www.doctorsclinicblog.com/tag/zika-virus

Thank you for the very informative post!

Have studies been conducted on what exists in the immune population that does not in the general population? How has the virus been around in the human population since 1968 and so little research has been conducted in regards to the virus? The virus originated in Africa, from my understanding. Have they not experienced the same problems that Brazil is now experiencing? If so, what was done to help them and if not, then why? Do they carry immunity of some sort?

Pingback: Zika Virus Bali Travel - Zika Virus

Pingback: Radio Show Links 1-29-15 – Evidence Based Errata

Pingback: Zika Virus Bali Symptoms - Zika Virus