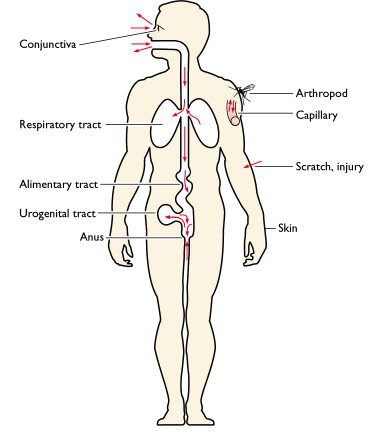

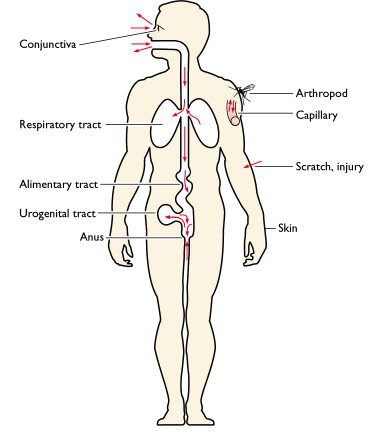

Now that we have a rudimentary understanding of influenza virus replication, we can begin to consider how the virus causes disease – a field of study called viral pathogenesis. The first step in this process is virus entry into the body.

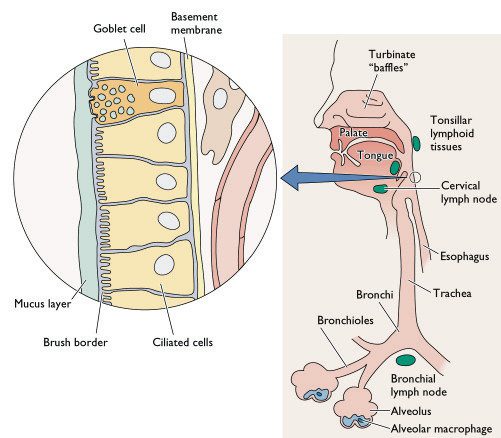

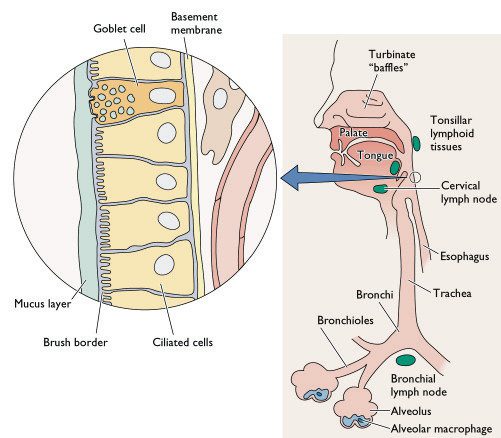

The respiratory tract is the most common route of viral entry, a consequence of the exposed mucosal surface and the resting ventilation rate of 6 liters of air per minute. The huge absorptive area of the human lung (140 square meters) also plays a role. Large numbers of foreign particles and aerosolized droplets – often containing virions – are introduced into the respiratory tract each minute. The reason why we are not more frequently infected is that there are numerous defense mechanisms to protect the respiratory tract. Mechanical barriers abound – for example, the tract is lined with a mucociliary blanket comprising ciliated cells, mucus-secreting goblet cells, and subepithelial mucus-secreting glands. Foreign particles that enter the nasal cavity or upper respiratory tract are trapped in mucus and carried to the back of the throat, where they are swallowed. If particles reach the lower respiratory tract, they may also be trapped in mucus, which is then brought up and out of the lungs by ciliary action. The lowest reaches of the respiratory tract – the aveoli – are devoid of cilia. However, these gas-exchanging sacs are endowed with macrophages, whose job it is to ingest and destroy particles.

As we discussed previously, viruses may enter the respiratory tract in aerosolized droplets produced by coughing, sneezing, or simply talking, singing, or breathing. Infection may also be spread by contact with saliva or other respiratory secretions from an infected individual. The larger aerosol droplets land in the nose, while smaller ones may venture deeper into the respiratory tract, even as far as the aveoli.

For a virus to successfully establish an infection in the respiratory tract, it must avoid being swept away by mucus or engulfed by alveolar macrophages. Then there are the more specific immune mechanisms that may intervene – a topic we’ll consider later. Suffice it to say that if a virus establishes an infection in the respiratory tract, it has surmounted a number of formidable barriers which ensure that we are not continuously infected.

What about the arthropod!!??

Is flu transmitted by insects? It would seem odd if it didn't.

There is no evidence that influenza virus is transmitted by insects.

It seems odd, given the prevalence of the virus in birds, but it does

not replicate in an insect host and therefore is not transmitted by

this route.

What about the arthropod!!??

Is flu transmitted by insects? It would seem odd if it didn't.

There is no evidence that influenza virus is transmitted by insects.

It seems odd, given the prevalence of the virus in birds, but it does

not replicate in an insect host and therefore is not transmitted by

this route.