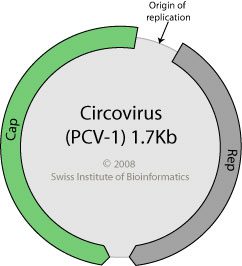

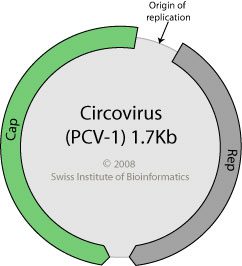

Porcine circoviruses are small, icosahedral viruses that were discovered in 1974 as contaminants of a porcine kidney cell line. They were later called circoviruses when their genome was found to be a circular, single-stranded DNA molecule. Upon entry into cells, the viral ssDNA genome enters the nucleus where it is made double-stranded by host enzymes. It is then transcribed by host RNA polymerase II to form mRNAs that are translated into viral proteins. There is some evidence that circoviruses might have evolved from a plant virus that switched hosts and then recombined with a picorna-like virus.

Porcine circoviruses are classified in the Circoviridae family, which contains two genera, Circovirus and Gyrovirus. There are two porcine circoviruses, PCV-1 and PCV-2; only the latter causes disease in pigs. Infection probably occurs via oral and respiratory routes, and leads to various diseases including postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome, and porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome. Virions are shed in respiratory and oral secretions, urine, and feces of infected pigs. Other circoviruses may cause diseases of birds, including psittacine beak and feather disease, and chicken infectious anemia, the latter caused by the sole member of the Gyrovirus genus. There are also circoviruses that infect canaries, ducks, finches, geese, gulls, pigeons, starlings, and swans.

We have no good evidence that porcine or avian circoviruses can infect humans. In the United States, porcine circovirus sequences can be detected in human feces. These most likely originate from consumption of pork products, most of which also contain porcine circoviruses. Circovirus sequences have also been found in commonly eaten animals such as cows, goats, sheep, camels, and chickens. Outside of the United States, the circoviruses found in human stools do not appear to be derived by meat consumption and might cause enteric infections.

Recently both PCV-1 and PCV-2 sequences were detected in Rotarix and RotaTeq, vaccines for the prevention of rotavirus disease in infants. The source of the contaminant was trypsin, an enzyme purified from porcine pancreas, which is used in the production of cell cultures used for vaccine production. Use of these vaccines was temporarily suspended, but resumed when the Food and Drug Administration concluded that there is no evidence that porcine circoviruses pose a safety risk to humans.

The good news is that porcine circoviruses in Shanghai’s waters are no danger to humans. But it is not a good idea to have rotting pig carcasses in a river that supplies some of Shanghai’s drinking water.

Circovirus seems to be part of the story here, but probably not the whole thing. See, for example, this story from a Chinese news outlet (in English):

http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/768685.shtml#.UUi60RljE18

Apparently some of the carcasses have tested positive for porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, a coronavirus, while others have had circovirus and still others haven’t had anything the authorities could identify. It sounds like there’s some larger animal husbandry problem going on at the farms around Shanghai, and the viral infections and resulting pig soup are just a manifestation of it. Investigative journalism and transparency about public health aren’t exactly China’s strong suits, so it could take awhile for all of the relevant facts to emerge.

Interesting. PEDV is no joke either: it causes severe enteritis, vomiting, watery diarrhea, and weight loss and is generally bad for the swine industry because the mortality rates are high. Do we know whether the circovirus found in the pigs was PCV-1 or PCV-2? Most pigs have the former and it’s not pathogenic. Those of us who eat pork consume PCV-1 on a regular basis. Either way it was a good reason to write about circoviruses.

This is an interesting story. I, like Alan suspect other factors are coming into play here, as PCV typically does not cause overt disease. The real effects come when there are co-infections with agents such as PRRSV or SIV, which I have not seen reported.

I am under the impression that PCV-2 can be pathogenic on its own in pigs, although there are certainly asymptomatic infections and exacerbations by co-infection. See for example http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23398668.

According to ProMedMail (http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20130312.1583338) PCV-2 was detected in the pigs from the river. They conclude: “The current reported identification of porcine circovirus PCV2 is, thus, not surprising. On the other hand, its exclusive or main role as the causative agent of the current problem has yet to be established, excluding other candidates such as FMD, CSF, and PRRS.” That’s foot-and-mouth disease virus, classical swine fever virus, and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus.

That ProMedMail link should be http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20130314.1586889

Interesting, thank you for passing on the article!

Pingback: TWiV 225: Transcripts from the inbox

I remember, when it started in China in 2007 – millions (2M?) of dead pigs, pork prices

redoubled, we were afraid it could be H5N1. They called it “blue ear disease”

It’s very hard to reproduce PCV-2 related diseases like PMWS (post-weaning mutisystemic wasting disease). Most of times in research, it is done it by co-infecting with PRRSV or giving an adjuvant. Aparently some kind of activation of the immune system is necessary to kick-start the loss of lymphocytes in lymphoid tissue and the granulomatous inflammation in these organs. Also, pathology seems more related to certain kinds of breeds, which suggests a genetic predisposition. Could explain why there are a lot of problems in china with porcine circovirus type 2. It’s also resistant as hell (just a capsid made out of beta sheets and 1.76kb of nucleotides), which also explains why you can find it anywhere you look. Since 5 years a vaccine is available, which has shifted all porcine virology resources to PRRSV. Such a shame because it is indeed a remarkable virus!

Anyway, keep up the good work

Nicolaas Van Renne

DVM

Pingback: Animal Farming: A case study of China | Commercial Farming

Pingback: Animal Farming: A case study of China | Commercial Farming

Pingback: Poultry Farming and its health impacts: A case study of China | Commercial Farming