One of the earliest cytokines produced is tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which is synthesized by activated monocytes and macrophages. This cytokine changes nearby capillaries so that circulating white blood cells can be easily brought to the site of infection. TNF-α can also bind to receptors on infected cells and induce an antiviral response. Within seconds, a series of signals is initiated that leads to cell death, an attempt to prevent the spread of infection.

Inflammation is a very prominent response to TNF-α. There are four typical signs of inflammation: erythema (redness), heat, swelling, and pain. These are a consequence of increased blood flow and capillary permeability, the influx of phagocytic cells, and tissue damage. Increased blood flow is caused by constriction of the capillaries that carry blood away from the infected area, and leads to engorgement of the capillary network. Erythema and an increase in tissue temperature accompany capillary constriction. In addition, the permeability of capillaries increases, allowing cells and fluid to leave and enter the surrounding tissue. These fluids have a higher protein content than the fluids normally found in tissues, causing swelling.

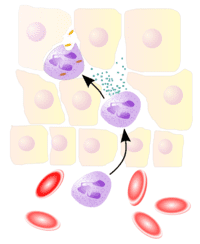

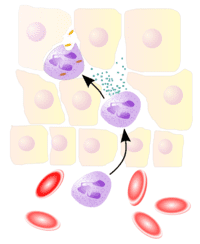

Another feature of inflammation is the presence of immune cells, largely mononuclear phagocytes, which are attracted to the infected area by cytokines. Neutrophils are one of the earliest types of phagocytic cells that enter a site of infection, and are classic markers of the inflammatory response (illustrated). These cells are abundant in the blood, and usually absent from tissues. Together with infected cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages, they produce cytokines that can further shape the response to infection, and also modulate the adaptive response that may follow.

The precise nature of the inflammatory response depends upon the virus and the tissue that is infected. Viruses that do not kill cells – noncytopathic viruses – do not induce a strong inflammatory response. Because the cells and proteins of the inflammatory response come from the bloodstream, tissues with reduced access to the blood do not undergo the destruction associated with inflammation. However, the outcome of infection in such ‘privileged’ sites – the brain, for example – may be very different compared with other tissues.

As expected, the inflammatory response is highly regulated. One of the critical components is the ‘inflammasome’ – very large cytoplasmic structure with properties of pattern receptors and initiators of signaling (e.g. MDA-5 and RIG-I). Recent experimental findings demonstrate that the inflammasome is critical in innate immune response to influenza virus infection, and in moderating lung pathology in influenza pneumonia.

Thomas, P., Dash, P., Aldridge Jr., J., Ellebedy, A., Reynolds, C., Funk, A., Martin, W., Lamkanfi, M., Webby, R., & Boyd, K. (2009). The Intracellular Sensor NLRP3 Mediates Key Innate and Healing Responses to Influenza A Virus via the Regulation of Caspase-1 Immunity, 30 (4), 566-575 DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.006

Allen, I., Scull, M., Moore, C., Holl, E., McElvania-TeKippe, E., Taxman, D., Guthrie, E., Pickles, R., & Ting, J. (2009). The NLRP3 Inflammasome Mediates In Vivo Innate Immunity to Influenza A Virus through Recognition of Viral RNA Immunity, 30 (4), 556-565 DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.005

Very nice. I enjoyed reading this a great deal.

I'm curious how topical cortisone (specifically cortisone inhalers used for asthma) affects this. If I understand correctly, cortisone decreases the production of a wide range of inflamatory signaling chemicals, and also decreases the numbers of some cell types (mast cells and eosinophils) in the lungs. Is that likely to make your body's initial response to a flu infection slower or less effective?

Hi, albatross!

Yes, you're right. Cortisone (or the glucocorticoids in general) up-regulates (activates) the anti-inflammatory response and down-regulates (deactivates) the pro-inflammatory response.

Asthma, which is a combination of inflammation and airway obstruction due to bronchial muscle spasm is usually treated with steroids and/or the other anti-asthma non-steroid drugs like the beta-2 agonists (terbutaline and albuterol/salbutamol).

Among the bad (or good, depending on how you use it) effects of glucocorticoids is the suppression of the immune system to mount a defense against infectious agents. So this is why doctors usually limit the intake of steroids unless it is very necessary. It would not be only the flu that the patient would be at-risk, but also fungal infections (candidiasis), and tuberculosis as well.

my assigment topc is inflammatory response, wat should i do?smbody can help me?

How about in H1N1 and its apparent massive inflamatory response. This would increase the alveolar capillary membrane thickness. Add this to the epithelial cell ulceration occuring . Its seems that this is the cause of the severe hypoxemia. My question is are we treating the underlying cause of hypoxemia? I feel that these patients should be hit with high dose antihistamines and an inhaled steroids such as pulmicort as frequently as possible. This may get the patient thru the massive inflammatory response which seems to be the culprit to so many deaths in H1N1. Maybe it will buy the patients enough time to tackle the virus which is supposed to be self-limited in nature anyways if the hypoxemia did not get in the way so much.

How about in H1N1 and its apparent massive inflamatory response. This would increase the alveolar capillary membrane thickness. Add this to the epithelial cell ulceration occuring . Its seems that this is the cause of the severe hypoxemia. My question is are we treating the underlying cause of hypoxemia? I feel that these patients should be hit with high dose antihistamines and an inhaled steroids such as pulmicort as frequently as possible. This may get the patient thru the massive inflammatory response which seems to be the culprit to so many deaths in H1N1. Maybe it will buy the patients enough time to tackle the virus which is supposed to be self-limited in nature anyways if the hypoxemia did not get in the way so much.

The similarity with cytokine response…viral/vs/mycotoxin is of Steven King books.

This is half off the subject, yet bio/micotoxins cause the same dreded response & after long exposure durations, MSH production can shut down causing hell on Earth over reactive immune response, as I am dying from.

http://www.moldvideos.blogspot.com

Steroids/cortozone have been known to deplete the immune system in the long term..

I know a mold victim with an immune level of 1, when 600-700 is average.

Roids seem like a favorite, but long term effects are risky.

http://www.biotoxin.info

http://www.moldwarriors.com/glossary.cfm

From what I ready in Times magazine, scientists at the Oxford Academy came up with a method of treating the inflammatory issues using anabolic steroids. They're preparing a new drug that should be available for the public in 2012.

A very informative article, thanks! I wonder whether chronic inflammation that occurs below the surface without discernible heat, swelling and pain follows a similar process if it’s caused by an infection? And what are the differences? Thank you for any advice. Cheers.

Looks like you’ve done your research very well.

Hi to every , as I am truly eager of reading this blog抯 post to be updated regularly. It consists of fastidious material. defiance gold http://www.mmogm.com/defiance/